What Realistic Utopia is Not

I. Shortcomings of past communal, national, and universal utopianisms

Under construction

II. The misuse by others of the term Realistic Utopia

John Rawls’ “Realistic Utopia” is characterized by mental pitfalls that Utopian Realism must avoid. Rawls is discussed below in an excerpt from ‘Cognitive Civilization’ (Yasutaka Aoyama, 2005, Kyoto University).

Cognitive Civilization is a new explanatory framework for the social sciences, synthesizing cognitive linguistic concepts with socio-historical theory to better understand causal links between historical phenomena and the cognitive processes underlying those phenomena. After discussing how the Platonic style of conceptual dichotomizing underlies much political thinking about society and historical events, the discussion turns to how Aristotelian methods of logic are likewise used to interpret and justify foreign policy decisions. While there may be some unfamiliar terms below that assume some knowledge of cognitive science or logic, it is hoped that the general outlines of the argument can nevertheless be followed.

9.2 Analogical Inference and Aristotle’s Syllogistic Mantle

The Platonic schema, however important, is but one instance of how philosophical systems merge with metaphors and linguistic constructions to shape our views and responses to the world. Other conceptual schemas may also tend to make it easier to feel that some deserve justice more than others, and that there is a simple way to determine that―as found in the writings of the philosopher laureate of the Clinton era, John Rawls. His seemingly comprehensive Aristotelian approach in The Law of Peoples (1999), with its five fold categorization of humanity, is a good example of the power of epistemological culture and methodology to overwhelm the unruly cries of reality.

Rawl’s apparently reasonable idea of “justice as fairness” to be meted out by “reasonable, liberal peoples” in “well-ordered democratic societies”, contrasted to “outlaw” and “burdened” states, merges marvelously with the aforementioned (in the preceding section) concept of the “indispensable nation”. The liberal, reasonable nation is indispensable in determining who are 1) the outlaw states that deserve punishment, 2) the “burdened states” requiring economic intervention, and 3) what Rawls calls the tolerated “Kazanistans” of the world, those decent but socially backward nations that are to be left alone.

Circular reasoning revolves among superordinate categories: “liberal peoples” are “reasonable”, therefore “justice” follows (1995:25), which is not much different from saying reasonable people are reasonable and therefore they act reasonably, definitions derived deductively almost like algebraic tokens in a solipsistic equation. At best, we might call it a form of inferential reasoning which Aristotle called apogee―a kind of logical extrapolation hardened into conviction by the reasonableness of intermediating links along the way, or what Charles Sanders Peirce (1940) would later rename “abduction―but stretched to the extreme.

In an act of moral wind-waving, Rawls conveniently defines away self-serving intentions in the actions of liberal, constitutional democracies against other states (1997:47), even if we are all well aware that such motives are an inseparable part of organized human nature. For such nations, so as there is license for unilateral economic intervention, so too there is a license for military intervention. “Just war” can be waged justly only by just, well-ordered peoples, where membership in that club of justice is determined by―guess who―those same just, well-ordered people. According to Rawls, the governments of such peoples can nevertheless conduct “grave wrongs”, but are excused by the need for “supreme emergency exemption”. ―Grave wrongs by others make them outlaw states; grave wrongs by the indispensible nation are simply “failures of statesmanship”.

Furthermore, the lack of concreteness and low degree of specificity in parameters allows Rawls’s model to be manipulated to fit almost any situation, so that if ever a just, well-ordered nation and a Kazanistan type nation clash, the model’s control inevitably goes to the strong. Perhaps unconsciously, that is the whole point of his mental excercise; for there is no section titled ‘Unjust War’ (as there is for “Just War”)― a possibility he perhaps wishes to avoid delving into, as it might force him to face his own logical shortcomings.

As studies of analogical reasoning (Markham and Gentner 2005; Perrott et. al 2004) show, the characteristics of an idealized category like those above, such as “liberal peoples”, become associated with the target analog, whether or not the target actually has those qualifications. The target space ‘absorbs’ the qualities of the source domain, and the mind naturally makes the implied inferences. In other words, once his own country can reasonably be called a reasonable, liberal democracy, then its follows its people are also “cooperative”, “moral”, and “well-ordered”, which in turn by definition means they wage just war―in a syllogistic version of “Ready”, “Aim”, and “Fire”.

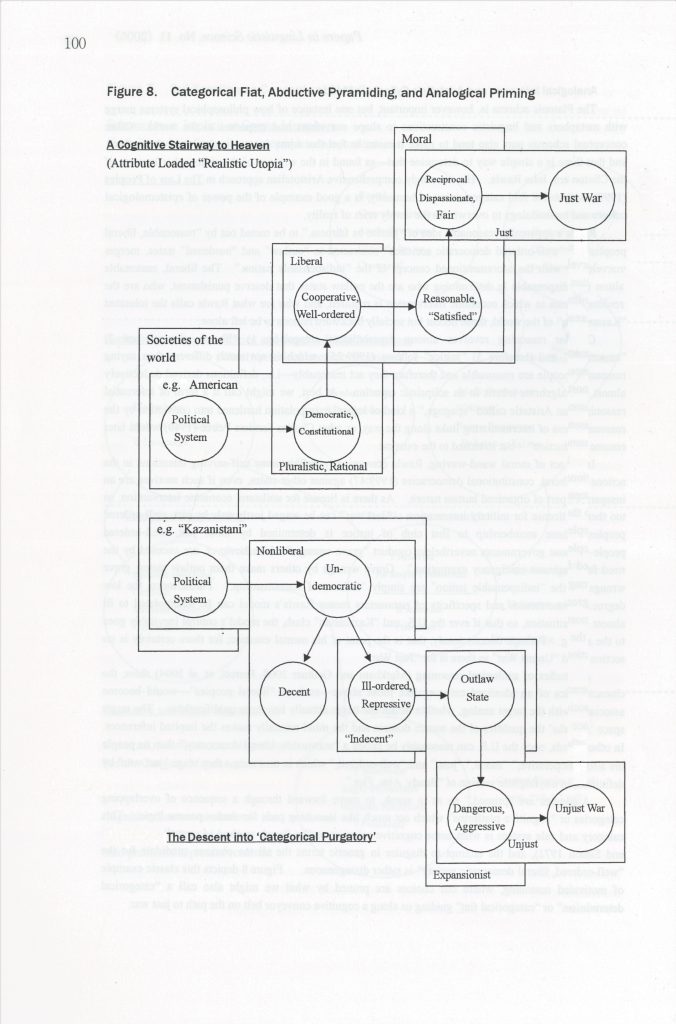

Analogies are primed, so as to speak, to move forward through a sequence of overlapping categories or what we shall call here ‘cognitive platforms’ which act much like launching pads for modus ponens logic. This category and rule system is what some cognition scientists call a “weak method of reasoning” (Newell and Simon 1972) and the attempt to disguise in generic terms the all too obvious candidate for the “well-ordered, liberal democratic society” is rather ingenuous. Figure 8 (simplified here) depicts this classic example of motivated reasoning, where our choices are pruned by what we might also call a “categorical determinism” or “categorical fiat“ guiding us along a cognitive conveyor belt on the path to just war.

There is something amiss with defining which people are decent in some sort of honorary perpetuity according to distilled Aristotelian essence or rarified Platonic principle. Every nation is simultaneously both decent and indecent, or decent at times but inevitably indecent at other times―regardless of its politcal system. Meaningful justice must have an element of open-ended empathy that does not predetermine the focal point of compassion; fair judgement is based on the facts of the matter at hand, not by a presumptuous pre-placing of nations in a fixed hierarchy of ethical categories. ―Now that is the very antithesis of jurisprudence, no less so than a court of law prejudging the outcome of a case based solely on the curriculum vitae of the plaintiff and defendant. ….

In the final analysis, all of Rawls’s definitions of peoples and international relations simply follow an idealized version of the status quo of the era he was writing in, what may be called an epoch of ‘centrifugal globalization’, otherwise obliquely referred to by Rawls as “Realistic Utopia”. His is a classic example of reformulating specific purpose into general abstraction for the sake of furthering that specific purpose. His blending of self-made definitions, moral ought-to-bes, and claims to realism about hypothetical situations is a nightmare of hocus-pocus―modus ponens, custom made for political manipulation.

If it were not for the aura of legitimacy that Rawls’ Aristotelian mantle provides, we would all see that he is a philosophical emperor with no clothes. Although of course, he would disagree with this portrayal, which nevertheless is fair, if we were to follow his own style (Rawls 1971:13), according to a conception of “justice as fairness”, which naturally is to be taken no more literally than if we were to speak of “metaphor as poetry”.

Note: Realistic Utopia is certainly possible in the societies that Rawls champions; it is his ideas about Utopia that should be considered misleading.